Roger Bennett and Mike Stewart share an unlikely and remarkable story about the horror of war and an unbreakable friendship.

By Jim Muir

Earlier this year, two men sat across the table from each other in the kitchen of a beautiful home nestled on the serene shore of Lake Moses, located northeast of Benton, IL.

To an outside observer this could have been two old friends, reminiscing over a cup of coffee or maybe just talking about sports, politics or life in general. But, this day, this meeting, this discussion went much, much deeper than casual conversation.

This day – May 8 – was a red-letter anniversary date that forever linked these two men – Roger Bennett, of Benton, and Mike Stewart, of Tacoma, Washington – together forever. It’s also a life-changing date that is seared in their minds forever. In 1968 the population of the United States was 200 million, and from that number Bennett, from the farmlands of the Midwest, and Stewart, from the sun and surf of California, shared a moment in time in the dark jungles of Southeast Asia. It’s a moment that has twists and turns, ups and downs and plenty of uncertainty.

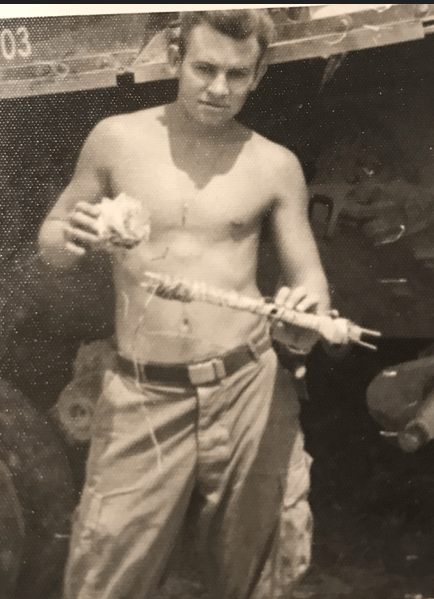

Mike Stewart, left, and Roger Bennett, right, are pictured on May 8, 2025, in Benton, IL – the 57th anniversary of a grenade blast in Vietnam that changed both of their lives forever.

In order to properly tell this story, you must first rewind the calendar back 57 years to May 8, 1968. The location is Vietnam, during the brutal TET Offensive, at perhaps the height of conflict that all total claimed the lives of 58,000 American soldiers. Ironically, Bennett and Stewart had taken completely opposite paths that led them to this fateful afternoon on this scorching hot May afternoon. Bennett, a 1965 graduate of Benton High School, was working as an apprentice iron worker in St. Louis in 1966 when he was drafted into the U.S. Army. He turned 19 in September that year and was drafted the next month.

Bennett did his basic training at Fort Carson, Colorado and was then sent back there for tank training.

“I spent a year total (including basic training) at Fort Carson and I was drafted for two years,” Bennett said. “After a year had passed, I started thinking I might not go to Vietnam, and that would have been fine with me. And then two weeks later we got notice and they sent our entire outfit there.”

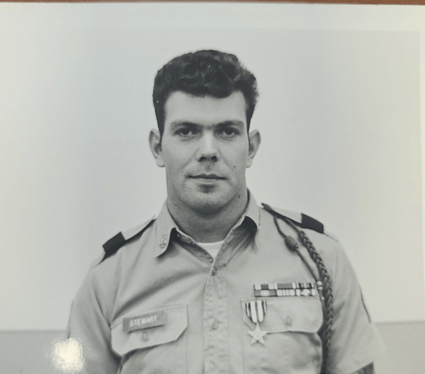

Stewart enlisted in the Navy in 1963 at the age of 17 and was discharged at age 20.

Stewart said he left the Navy because they wouldn’t send him to Vietnam. So, after his discharge from the Navy he enlisted in the Army and shortly thereafter found himself in Vietnam in the same unit with Bennett.

“I wanted to go to Vietnam,” he said. “It was going on at the time and I felt like I had to go and see what it was all about.”

When the conversation shifted to the importance of the meeting between Bennett and Stewart on the specific date of May 8, both men became emotional, stopping often to regain their composure and wipe away tears. Clearly, for both men the emotions of that fateful day nearly six decades ago are still very close to the surface.

On the afternoon of May 8, 1968 Bennett and Stewart were given instruction to respond to help another unit that was hunkered down and under sniper fire. The plan was to take a tank into the area to give the other unit cover so they could escape the enemy fire.

Stewart was the tank commander and Bennett was at the controls and there was an infantry unit traveling on foot behind them. Bennett said he had a “bad feeling” that “something wasn’t right” when the tank didn’t encounter any enemy fire, even after moving deep into the area.

What Bennett and the rest of his unit didn’t know is that the Viet Cong were waiting until the tank got in range of a rocket-propelled-grenade (RPG) to open fire.

“All total, we were hit five times by RPG and the last one is the one that got Mike,” said Bennett. “It came in through the turret and it really did some damage.”

A turret on a tank, is best described as the rotatable structure mounted on top of the hull, that houses the main gun and the crew responsible for operating it. It allows the gun to be aimed and fired in any direction without needing to move the entire tank.

“I looked and saw that Mike was covered in blood, there was blood everywhere,” said Bennett. “I knew we had an infantry unit behind us, but I just threw it in reverse and floored it.”

After behind hit in numerous places from the RPG, Stewart recalled those harrowing moments before he lost consciousness.

“I just remember that I was trying to talk…and couldn’t…and I was trying to move my arms…and couldn’t,” he said. “I thought I was either dying or I was already dead.”

In all, Stewart received wounds in the armpit area under both arms, in the back, the stomach and the crotch area. Stewart spent four months in the hospital, the first six weeks in and out of consciousness and near death. He had more than 40 inches of scars to close the wounds. After being released from the hospital, Stewart was sent home and received his discharge from the Army in 1970.

Because communication in 1968 was nearly non-existent based on 2025 standards, Bennett’s attempts to find out how badly his tank commander had been injured were limited.

“I asked one of the medics how “Stew” was and his reply while he shook his head side-to-side was, “not good,” Bennett remembered. “That was usually the response we got when somebody didn’t make it. I saw them putting him in a body bag, so I thought he was dead.”

Bennett emphasized that his reaction to what he thought had happened to Stewart was not calloused, but simply the only way to deal with his current surroundings.

“You couldn’t dwell on anything or be distracted because we had people trying to kill us every day,” said Bennett. “Everybody’s goal was to try and stay alive another day.”

After his discharge Bennett tried unsuccessfully a few times to find out any information about Stewart and for more than 50 years believed that the tall, curly-haired tank commander had been killed right in front of him.

In all, Stewart received the Silver Star, Bronze Star and three Purple Hearts because of his actions that day and the wounds received. Bennett received a Purple Heart and the Medal of Valor for climbing into the burning tank and getting Stewart out. Ironically, it was the honors Stewart received that opened the door for Bennett to begin the task of trying again to find Stewart. During a conversation in 2018 with another veteran from his unit, Bennett was told about the Silver Star award and mentioned the name of Mike Stewart. Still not certain it was the same one, Bennett was able to obtain an address and promptly fired off a letter with the information he was looking for and he included his phone number.

Bennett said he received a phone call from Stewart a few weeks later and even during the early minutes of the call he was not certain that the person he was talking to was the same person he had served with during his days in Vietnam. He said there was an amusing exchange during the early minutes.

“He asked me what the guy named Mike Stewart he served with looked like,” said Bennett. “I told him he was tall and curly-headed and a nice-looking guy,” said Bennett. “When I said that, he said ‘and he’s still a nice-looking guy.’ When I told him the guy I served with had been in the Navy before enlisting in the Army, we pinned it down that he was in fact that same guy.”

Bennett said it was a surreal moment to go from believing Stewart had been dead for 50 years to talking to him on the phone.

“When I found out “Stew” was alive I was thrilled,” Bennett said. “I thought he was dead for 50 years. We were only together for a short time but he was the tank commander and he kept us alive. So, when I found out he was alive the first thing I wanted to do was get in contact with him and make a plan to get together.”

Stewart said he and Bennett talked on the phone a couple times a year during the past seven years – always on May 8 – but decided this past year to hold a reunion. Stewart and his wife Karen traveled by train from Tacoma to Benton to spend a few days with Bennett and his wife Robin.

While Bennett and Stewart took different paths to get to Vietnam, they also took very different paths after they were discharged from the military. Bennett worked 10 years for Best Buy in sales and then took a job in sales with Reader’s Digest, where he became one of the top salespersons in the nation. Roger and Robin are the parents of two children, Christian and Courtney.

For Stewart, the path was not as easy and putting Vietnam and his near-death experience behind him became a daily battle.

“You can’t block out what happened to you,” Stewart said, his voice cracking with emotion. “I can drop back into that time in a moment. I would get very angry, very easily. People would say, ‘why don’t you just forget that war?’ It wasn’t quite that easy. You came home and we were looked down on because we had been in Vietnam. We were never debriefed. I went to Vietnam by myself and I came home by myself. They didn’t send you in units like they do now, they sent you one person at a time. I couldn’t turn it loose.”

And from those emotions came other battles as Stewart fought drug addiction, which eventually led to a 42-month stint in federal prison for drug trafficking. He was released in 1977 and has had no issues since.

Bennett said he also had difficulties making the adjustment back to civilian life.

“I was angry when I got home and I became angrier when I learned that the war was more political than anything else,” said Bennett. “I tried to put it behind me as best I could. I remember when I came home, I was walking on the Benton Public Square and a car backfired and I hit the ground. I remember walking through the airport in San Diego and somebody shouted “baby killer” at me. There was certainly no warm welcome when we got home.”

Bennett said he also has experienced issues through the years about the “why” question of how he survived Vietnam.

“There was 12 of us that went to Vietnam together and only two of us came back home,” he said. “These were guys I had been with every day for a year and they got killed over there. I see their faces every single day. Why did I come back and they didn’t? You can’t get those thoughts out of your mind, no matter how hard you try.”

Through a trembling voice, Bennett then recited the last names of all those killed. “Yeah, let’s just erase it and forget about it…you can’t.”

Stewart said finally reconnecting with Bennett after nearly 60 years has been a “wonderful blessing.”

“It’s bringing back a lot of memories but also establishing a friendship I never did get to follow through with,” said Stewart. “What Roger has given me by this meeting is something I really needed and it’s something very special. His actions that day saved my life and is the reason I am here today.”

Bennett said when the entire story is put together, the reunion of two old Vietnam veterans is “nothing short of remarkable.”

“You have to keep in mind that I spend almost my entire life thinking “Stew” was dead, the last time I saw him they were putting him in a body bag,” Bennett said. “And then to get to meet him and share stories and memories is a tremendous blessing.”

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.